I am unusual among academic physicians in that I not only did my residency at the same medical school I attended, but I then joined the faculty at that medical school. Thus, I have been on the medical staff of our teaching hospital for over 40 years! It has been interesting to see the changes in the work environment over these decades, which I suspect are typical of all hospitals across the nation. Back in the day, the hospital was a bustling place, with doctors, nurses and staff going to and fro. Groups of people in scrubs and white coats huddled around the nurses’ station, particularly near the large merry-go-round rack where the patients’ charts were stored. There was constant chatter as people discussed cases, made treatment plans and plotted out their day. Knots of doctors were in the halls as they did rounds and met up with the consultants they had called in. In those days, there were two or even four patients in a room.

Our teaching hospital has added new buildings and renovated the older ones; some of the wards I worked on have been converted to administrative space. The new parts of the hospital are beautiful. Every patient is in a single room with excellent sound proofing. The hospital is full every day, with people waiting in the emergency department to take the next bed. To walk through the halls, however, one would think the hospital is empty. Doors to the patients’ rooms are closed, workstations in the hall are deserted, and only occasionally can a nurse be seen pushing a computer on a cart as they move from room to room. Hospital teams consult each other by entering a request in the electronic medical record (EMR) and then paging the needed team. In my time, we would go to see the patient, review the paper chart, write a (usually) brief note and then meet the consulting doctor in the nurses’ station or hallway to discuss our recommendations. Needless to say, this process has gone the way of the dinosaur. Consultants now see the patient and “drop a note” in the EMR. The patient’s doctor hopefully reads the note and finds the recommendation useful. The consultant and the consultee will speak only if they “need to” and will do this by phone or text, rarely in person. HIPAA is responsible for many of these changes -- quiet hallways and sound proofing reduce the chance that confidential health information is overhead by others.

I spent all my career as an outpatient psychiatrist, but I took call to supervise the residents on weekends and, on occasion, when the consultation faculty were on vacation. It was here that I came face-to-face with how much things have changed since my early days. First off, the residents have “table rounds” where they discussed cases with the attending and often did not feel a need to see the patient. They read the nursing and medical notes in the EMR (as well as the laboratory findings) and that got them up to date on the patient’s progress. One day when I was attending, a particularly difficult case presented itself. I felt that we should “talk to the team” since the recommendations we were to provide were nuanced. “Do you mean in person, Dr. Pliszka?” one of the residents asked. “Yes,” I replied and off we went. The internal medicine floor hallway was deserted (despite every room being occupied by a patient). In response to my question as to where we might find the patient’s internal medicine team, the lone nurse in the hallway replied, “They are most likely in the workroom.” My residents did not know where this workroom was; fortunately, the nurse pointed us to it.

The workroom door was solid wood with no markings on it and had an electronic lock. After several knocks it opened. I introduced myself and entered along with my two residents. About five medicine residents were in the room, each at their cubicles with the EMR open on their computers. The looks they gave me were similar to those you might get if you walked into the wrong gendered restroom by accident. I spoke to the intern in charge of the cases and described the complexities of the case, quickly detailed our recommendations and asked if she had any questions. The medicine residents looked at each other quizzically. “No questions,” the medicine intern said, “Just put it all in a note.” As we left, I could see the barely concealed smirks of my residents. I never again tried to “talk to the team” when I attended on the consult service.

Treating the patient or the EMR?

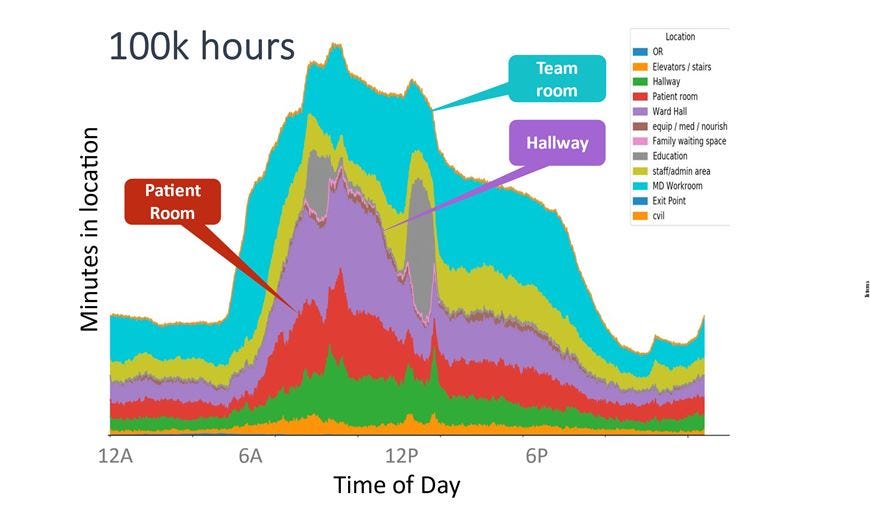

The fact that hospital resident physicians spend almost all their time in the workroom or administrative areas is now well documented in a study by Michael Rosen and colleagues. As shown in the figures below, the workroom, the hallway and the administrative area are where residents spend most of their day. As hospitals have increased in size, it is likely that hallway time mainly involves walking from one part of the hospital to another. I certainly found this to be the case when I attended on the consult service.

If physicians are communicating mainly by progress notes in the EMR, this brings us to the key issue I want to discuss: the increasing “progress note bloat” that is occurring in EMRs. What is causing this and is it good for patient care? When EMR emerged, they allowed (for better or worse) physicians to maintain the structure of the progress note that they had been writing for at least 150 years. The standard note involves the History of Presenting Illness (HPI), the Past Medical History (PMH), the Physical Examination, the Diagnoses (or Impressions), and the Plan (Treatment). Since the 1970’s, the Plan has been required to be “Problem Oriented.” In 1968, Lawerence Weed published the seminal article, “Medical records that guide and teach,” which is credited with the development of the Problem Oriented Medical Record (POMR). For nearly 60 years now, physicians have done a “Plan” section of their progress note that listed all the patient’s “problems” and the action for each one. What is the difference between a problem and a diagnosis? Like “How many angels can dance on the head of a pin,” medical students, residents and professors discuss this topic endlessly. In Weed’s philosophy, you use the level at which you understand the disease process. So, if a patient with known diabetes enters the hospital with high blood sugar, hypertension and diabetic foot ulcer (due to poor circulation), the note writer might put these as one problem (diabetes) and discuss the plan for (e.g., control the blood sugar). On the other hand, the foot ulcers will require treatment in addition to controlling the blood sugar. So, perhaps it should be a second problem? If the patient’s diagnosis is not clear, then the POMR philosophy says to create a separate problem for each symptom (chest pain, shortness of breath, rash, etc.) and then lay out the process you will use until the diagnosis is clear. Dr. Marc Aronson, one of Larry Weed’s mentees, laid out what Weed felt were the advantages of this approach:

“Writing plans so as to approach diagnoses by taking time to consider the differential diagnosis, monitor medication side effects, and order medicines in a logical and orderly manner, would not only improve patient care but would, Weed believed, also help doctors understand the nature of their patients’ diseases more completely. He thought, and further taught, that the medical record should guide and teach. And that if it was done well, it could be audited to determine if the care was thorough, reliable, analytically sound, and carried out in an efficient manner.”

Weed died in 2017, but the POMR became the mainstay of medical note writing. He developed the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS), a very early EMR and which heavily influenced the development of all EMRs.

What has EMR become? Dr. Weed might weep. Siddhartha Yadav and colleagues compared 250 EMR records to 250 paper charts in a health system that had transitioned to an EMR, limiting the charts to patients with five diagnoses with “invariable physical findings.” They could look at what the charts said versus what the patient actually had. The results were concerning:

“The rate of inaccurate documentation was significantly higher in the EHRs compared to the paper charts (24.4% vs 4.4%). However, expected physical examination findings were more likely to be omitted in the paper notes compared to EHRs (41.2% vs 17.6%). Resident physicians had a smaller number of inaccuracies (5.3% vs 17.3%) and omissions (16.8% vs 33.9%) compared to attending physicians.”

EMR notes were longer than paper notes. Intriguingly, EMR notes were written later in the day than paper notes. This is probably because doctors had to go back to the work room to do them and being longer, they needed to set aside time to do them. The authors gave an example of the inaccuracies they found: a stroke patient had left sided weakness (left hemiparesis), yet the EMR note read “No focal neurological deficit noted.” This most likely occurred because the doctor used a physical examination template (which can be pasted into the note) with all the normal findings as defaults; they then failed to go back and change the neurological exam to reflect the actual findings.

In 2021, Adam Rule and colleagues published an article asking, “How did the length and redundancy of outpatient progress notes change from 2009 to 2018?” They examined over two million progress notes from over 6000 authors across 46 specialties. The median note length over this time period increased 60%, and redundancy increased from 48 to 59%! By 2018, the average note had only 29% of content that was directly typed while 71% was from a template or copied and pasted. Younger physicians wrote longer notes, a phenomenon I have clearly noted among residents and junior faculty at my institution.

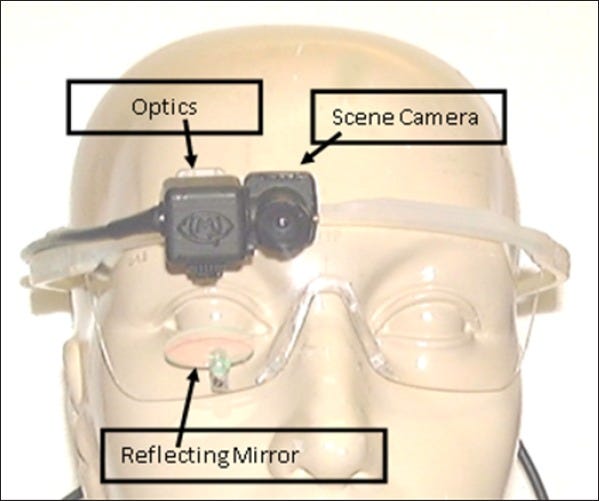

Many of my colleagues argue that while notes are longer, they are also now comprehensive and “document everything.” Surely, doctors read these comprehensive notes and they inform their care of the patient, right? P.J. Brown and colleagues actually hooked devices to ten hospitalists’ heads that tracked their eye movements when they were on the EMR:

The results do not surprise: the hospitalists spent almost all their time reading the impression and plan section, despite the fact that all the other sections (HPI, past history, exam, etc.) constituted two-thirds of the notes.

Why do I say I am not surprised? When I used to serve as an attending on either the consult or inpatient setting, the residents always commented that their consultees only read the Impression and Plan. So why write everything else? Here are some of the comments I got:

Our attendings require it.

It is for liability reasons.

We have to “document everything” or someone will accuse us of not “documenting everything.”

Faculty attendings will say all these things and say it was the way they were taught. They will also add, “because billing requires it.” But is this true?

Billing requirements are not to blame

The American health care system does have an odious cat-and-mouse billing system, meaning the doctors try to bill for the most legally possible while payors can challenge a billing. It is the “documentation” that determines who is right. Health care systems employ hundreds of “coders,” people whose job is to read the progress notes and determine if the service documented is of the required complexity level for the billing code the provider gave it. The difference in a level 3, 4 or 5 code for a service can be worth millions of dollars a year for a large health system. Prior to 2021, justifying a higher-level service required writing a very complex progress note, with multiple “elements” required in each section of the progress note (HPI, past history, exam, plan). This policy reinforced the development of complex EMR templates. After 2021, the American Medical Association changed the system such that the focus is on the treatment plan section alone, which also allowed doctors to bill for effort that may have occurred outside the patient visit (e.g., calling a consultant or reviewing prior records).

These changes meant that physicians have increased the number of higher-level codes they bill. One study showed that Level 3 (not complex) visits decreased as a percent of all visits after the new system was implemented while level 4 and 5 visits increased. With fewer documentation requirements, doctors reduced the size of their notes, right? Of course not. The authors looked at progress note length and time spent in the EMR and found “no meaningful changes.” Providers were doing the same amount of documentation even when billing did not require it.

The tyranny of the template: Is the EMR really to blame?

For the non-medical reader, the “template” in an EMR is essentially a structured Word document that gets pasted into the EMR blank text box. It has various stock phrases that doctors in a specialty use commonly and most often contains check boxes or drop-down tools to allow data to be inserted for the individual case. For instance, a template might say, “The patient’s mood is [Drop down].” The drop down might then contain the phrases, “depressed,” “elevated” or “anxious.” Specialties can set up templates for their clinic or department, but almost all EMRs allow individual providers to modify, add to, or create their own templates from scratch. Moreover, EMRs allow providers to copy a note from the last visit to the current visit, so the provider only needs to change the drop down or check boxes of those items that have changed. Providers may not be careful about doing so. As a result, the provider may neglect to change the drop down, leading to an inaccurate record. Ultimately, providers add more and more stock phrases, leading to longer and longer notes. In the end, a 15-minute office visit for a simple complaint can generate a four-page progress note.

I was heavily involved in implementing the EMR in our Department of Psychiatry and I strived to keep the templates in a minimalist state to ease documentation. It was mostly for naught, as providers kept adding to their individual templates. One of the graduates from our psychiatry program and a subsequent colleague of mine ended up as medical director of a large psychiatric outpatient clinic. All the psychiatric providers at that clinic agreed that the templates in their EMR were unmanageable. My colleague called a meeting of the providers to design a new template; he said that they would begin with a blank template and only add the sections that were clinically necessary. By the end of the meeting, the template was even longer than the original as each provider demanded their section of the template be included! Most said that no matter what the clinic template was, they would still use their own. These were the same people, my colleague noted, that complained about the amount of time they spent on the EMR.

Will Artificial Intelligence (AI) save us?

Most major EMRs have begun integrating AI into the note writing process. Typically, the provider will record the interaction between themselves and the patient, including the physical examination. As an example of the latter, after listening to the heart, the provider would dictate, “regular rate and rhythm, no abnormal sounds.” The provider will also dictate the diagnosis and plan. The AI will generate the written elements (HPI, Past History) as well as the physical examination and plan. The provider has the option of downloading the verbatim conversation with the patient or more likely, an AI-generated progress note which summarizes the provider-patient interaction. For psychiatry, this is likely straight forward for a medication management visit of an uncomplicated patient. But it would be interesting to look at what AI makes of a psychotic patient, a complex social history or a psychotherapy session. The provider must then check the note for accuracy. In the ideal world, the provider would not have to type or click on anything to enter the progress note. In theory, this should save time but challenges abound, particularly if providers must spend more time looking for AI-induced hallucinatory errors.

Physician (and other providers), Heal Thyself

By in large, providers need to shift the focus of blame regarding time spent on the EMR from the EMR itself and examine their own attitudes and assumptions about medical documentation. Medical schools, and the health professions in general, attract people who are detailed oriented, leading to a bias for the “trees over the forest.” The competitive process for admissions to health professional schools and residencies (standardized testing, essays, activities on one’s CV) strongly reinforces the ethic of “more is never enough.” This competitive streak extends to “who has done the best work up” and “who has the best progress note.” Those in teaching positions then feel obligated to pass their “best practices” to their mentees.

The growth of smartphones and texting has reduced in-person professional to professional discussions about patients, leading to a culture of “it’s in the note.” As a result, the progress note becomes even more important in in-patient care.[1] In mental health, we feel that each patient is very different from another, even if they have the same diagnosis; this leads to a lack of consensus as to what, besides symptoms and diagnoses, should be included. I was in a medical director role for nearly 30 years in my career. As EMRs grew more complex, I found providers asking to spend more time in “admin work,” that is, working in the EMR rather than seeing patients. Some providers would claim that they could not possibly see any more patients because they needed so much EMR time. I came to believe that the reverse might be true: people feel more comfortable sitting in their office or workroom banging away on an EMR than seeing more patients. This may be part of a disturbing trend in the world at large in which virtual activity is seen as more important than real-world interaction.

The Challenge of Medical Informatics

At the very least, AI will reduce the data input and free text that are necessary for providers to perform to complete progress notes. We need to move to the real challenge of medical informatics: how to transduce the patient’s experience into data points that reflect the progression of their illness and their response to treatment. If we simply replace over-templated notes with bloated or inbred AI notes, then we have not made progress. In the meantime, I have limited my template use in my progress notes. I still copy forward, but with a note small enough to be efficiently edited and kept accurate. When it comes to progress notes, less can be more.

[1]In the hospital, physicians must hand off to each other at the end of a shift. In teaching hospitals, this had led to handoff tools which must be kept up to date at the end of each shift. Invariably these diverge from what is in the EMR. The handoff tools are often printed out so residents can carry it around from place to place in the hospital. It is too much trouble to log in to the EMR on each floor of the hospital that the patient is on to directly view the EMR. This is because when you log onto a particular workstation for the first time, Windows takes so long to load!