Normality vs. Abnormality

How to Distinguish? Who Gets to Decide?

In Compact Magazine in November of 2024, Sohrab Ahmari has an interesting take on what is “normal” and who gets to define it. While Ahmari is concerned about “normality” in the political realm, he delves into the history of how the concept of normality emerged in medicine. This led me to think about how normality has been an evolving concept in psychiatry. It has become a more pressing issue as neurodiversity is a recent and widely discussed concept in mental health, with major implications as to how mental disorders are diagnosed and treated. Today, “Normal” and “Abnormal” are viewed by many, as the millennials would say, “judgy.” That is, calling something “abnormal” may be viewed as stigmatizing or discriminatory. In the research literature, we used to speak of “normal controls.” This has been replaced by “typically developing participants” in child studies and “healthy controls” in adult studies. In the end, however, we need to distinguish between people with a disease from those without it. So, what, exactly, is “normal?” As Ahmari writes:

“But through it all, normal remains ubiquitous and ineradicable. It’s a remarkable fate for a relatively novel label, contested by natural and social scientists almost as soon as they came up with it; one whose history is stained by relation to eugenics and some of modern medicine’s less-than-benevolent moments; but which remains an aspiration for most people.”

Ahmari cites the work of Peter Cryle and Elizabeth Stephens who noted that the word “normal” emerged in the 19th century among French anatomists who began observing the differences between organs from people with and without various diseases. The origin of the word “normal” is the Latin word, “normalis,” which originally meant “made to a carpenter’s square.” By late 19th and early 20th century, it acquired its modern meaning of “standard” or “average.” In 1809, the German mathematician Carl Friedrich Gauss used a gambling formula developed by Abraham de Moivre in 1733 to study errors in astronomical measurements. As a result of this, Gauss established the famous “bell curve,” which is called the Gaussian Distribution in his honor. Later, the Belgian statistician Adolphe Quetelet used the Gaussian Distribution to examine variables in the social sciences. In 1835, Quetelet published Treatise on Man, where he described his concept of the “average man,” characterized by the mean values of variables that follow a “normal (Gaussian)” distribution. (Quetelet was also the inventor of the Body Mass Index!)

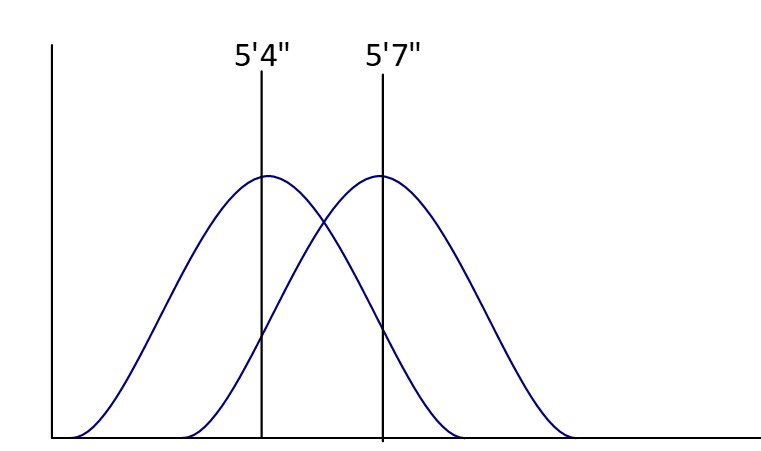

The normal curve can be more complicated than one might imagine. Let’s take the example of body temperature in people without a fever (temperature below 100.4° F). With modern thermometers, the human body temperature has a mean of 97.7° F (not 98.6° F) with 95% of non-febrile persons having a body temperature between 96° and 99° F. This means that body temperature and its bell curve are consistent all over the world and have been for generations. Height is a little different. What is the average height of a human? That varies according to which generation and region of the world about which you are referring. A man born in the Western world in 1896 would have an average height of 5’ 4” while a man born in 1996 would have an average height of a little over 5’7.” The standard deviation for both populations is about 3 inches, so the two bell curves would look like this on a graph:

The improved food and health environment in the developed world over a century has led to the “normal curve” of height being shifted to the right. For people at the extremes, we do not speak of them being “abnormally tall” or “abnormally short” unless they have a condition (e.g., pituitary tumor) that causes the extremes of height. So, we see that even with a simple variable like height, “normal vs. abnormal” is not a quantitative difference alone and that being abnormal has a clear qualitative aspect to it. One must look at more than just numbers on a scale. Thus, in health care, “abnormality” is not a moral judgment; it reflects some finding from the physical examination or laboratory work that may be related to disease. The goal of diagnosis is to initiate treatment for that disease and improve outcome, not to stigmatize the individual.

Things tend to be messier in the mental health arena. The 2nd edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-II) of the American Psychiatric Association (APA), issued in 1968, listed homosexuality as a psychiatric disorder; it was then removed from the DSM-II in 1973. Jack Drescher wrote a comprehensive history of this process. Robert Spitzer, a leading psychiatrist whose work would lead to the development of DSM-III, chaired an APA subcommittee examining the issue. Years later, he wrote that he had “reviewed the characteristics of the various mental disorders and concluded that, with the exception of homosexuality and perhaps some of the other ‘sexual deviations,’ they all regularly caused subjective distress or were associated with generalized impairment in social effectiveness or functioning.” Spitzer, perhaps unwittingly, created the modern definition of mental disorders. They either cause the individual to experience distress and/or impaired functioning. Most mental disorders do both but for each factor, a line must be drawn. How much distress is too much? What is our measure of social functioning? If we see a homeless person with schizophrenia who is freezing on the street and hallucinating, this behavior is clearly abnormal even if the person tells us they feel fine and don’t want help. But what about a child who makes B’s on schoolwork when the parent is sure they could make A’s if they just paid better attention? How do we draw the line to make the diagnosis of ADHD?

Psychiatry has always been more of a qualitative than a quantitative science, beginning with the theories of Sigmund Freud, whose work dominated mental health in the first part of the 20th century. Freud pioneered what remains a predominant view in mental health, even among therapists who reject classical psychoanalysis. That is, the mental health provider listens to the patient and is more attuned to the patient’s past social and personal history than specific mental health symptoms, which are viewed as an outward manifestation of deeper, underlying processes. The most recent variation of this is “Trauma-Focused Care” in which the patient’s history of trauma is seen as the major (or only!) explanation for their symptoms; providers speak of “being trauma-informed” or having a “trauma focused lens.” At about the same time that Freud was publishing his work, Emil Kraepelin was observing patients at various mental hospitals in Germany. Kraepelin and his associates began recording the patients’ symptoms on cards, observing not only the individual symptoms but how they changed over time. Three of Kraepelin’s cards on individual patients, published in his classic textbook of psychiatry, are shown here:

In the figure above, “Alter” means age in German (in years). Kraepelin noted changes in manic and depressive symptoms in these patients over time. As he accumulated his cards, he observed that patients fell into either of two major groups. “Manic-depressive” patients had alternating moods and better prognosis, while the patients in the other group had early onset, flattened emotions and social withdrawal. This latter group appeared to deteriorate cognitively with time, so Kraepelin characterized them as having “dementia praecox.” This fundamental distinction between these groups of symptoms and their course remains with us today as bipolar disorder and Schizophrenia. (In 1908, Paul Bleuler noted that the latter illness does not always lead to deterioration and suggested the term Schizophrenia to replace it.) Kraepelin’s approach competed with Freud’s throughout the first half of the 20th century, even though they saw very different patients. Kraepelin dealt with serious mental illness, while Freud focused on those with neuroses (or anxiety by modern definitions).

Unfortunately, Kraepelin was heavily influenced by the eugenics of his era and while he was not a Nazi, he was an anti-Semite. His most notorious student was Ernst Rüdin, who promoted sterilization and killing of people with mental illness. He was a Nazi party member, receiving the “Gothe Medal of Art and Science” in 1939 from Hitler himself. The role of German eugenics in supporting Nazi atrocities discredited biological psychiatry for decades afterwards and contributed to the rise of psychoanalysis in the post-war period. Indeed, the idea that all mental illness was purely psychological and curable through therapy alone spurred the deinstitutionalization movement in the 1960’s. Thomas Szasz opened the attack on “normal” in mental health with his books, The Myth of Mental Illness (1961) and The Manufacture of Madness (1970). According to Szasz, mental illness did not exist at all, it was just a different way of being. Szasz further argued that neurological diseases such as Parkinson’s Disease or stroke had physical correlates that validated them, while the lack of such findings in mental illness was “proof” of their lack of validity. After 30 years of research, no definitive biomarker of any mental illness has been found. How do we know that Szasz was wrong?

We can resolve this issue by using hypertension and ADHD as examples. There is widespread agreement among both scientists and the public that primary (essential) hypertension is a disease. While there is increasing acceptance of ADHD as a disorder, it remains controversial in many quarters. Traditionally, in medicine a disease is a condition for which the cause (pathophysiology) is well understood or established while a disorder is a collection of signs and symptoms where the pathophysiology is mostly unknown. The distinction is somewhat arbitrary. Let’s start with hypertension, defined by “objective” blood pressure readings:

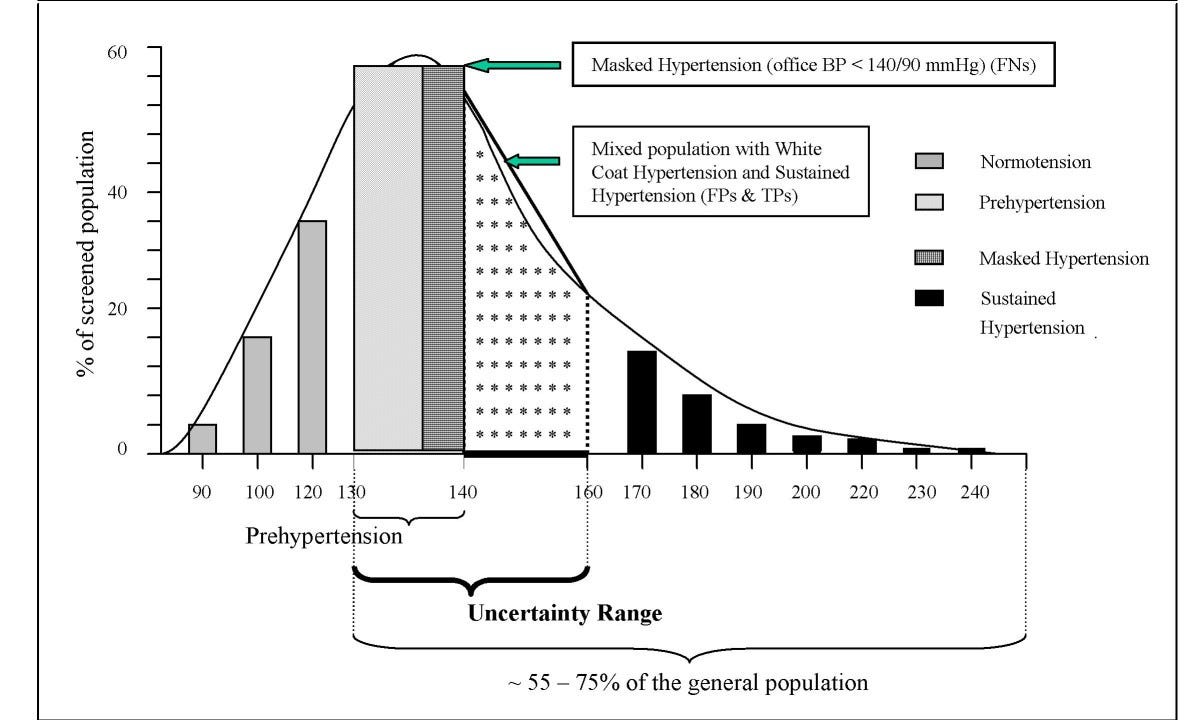

In this sample of patients, the average systolic blood pressure is around 130 mm Hg. The bell curve is skewed to the right because of the small number of people with marked or sustained hypertension. Between 130-160 mm Hg systolic, there are people who have “white-coat hypertension” as well as people whose blood pressure might be low in the office but possibly elevated at home. The authors put these people in an “Uncertainty Range.” At one time, 140/90 mm Hg was considered the cutoff for high blood pressure for people under 65 years old. This was lowered by the American Heart Association to 130/80 mm Hg in 2017. Where did these cutoffs come from? Scientists studied large datasets and clinical trials over decades and found that people with blood pressures above this level were more likely to suffer heart attacks, strokes and other cardiovascular disease. In contrast, people whose blood pressure was lowered to 130/80 with medication were less likely to suffer these consequences. Does hypertension have a specific cause? Do we understand its pathophysiology completely to determine that it is truly a disease? In fact, a single cause of hypertension has not been established. There are risk factors for hypertension, including genetics (30-60% of the variance), obesity, smoking, salt intake and activity level. These factors combine, in unclear ways, to lead to high blood pressure in up to 60% of people in the U.S. by the time they reach 65.

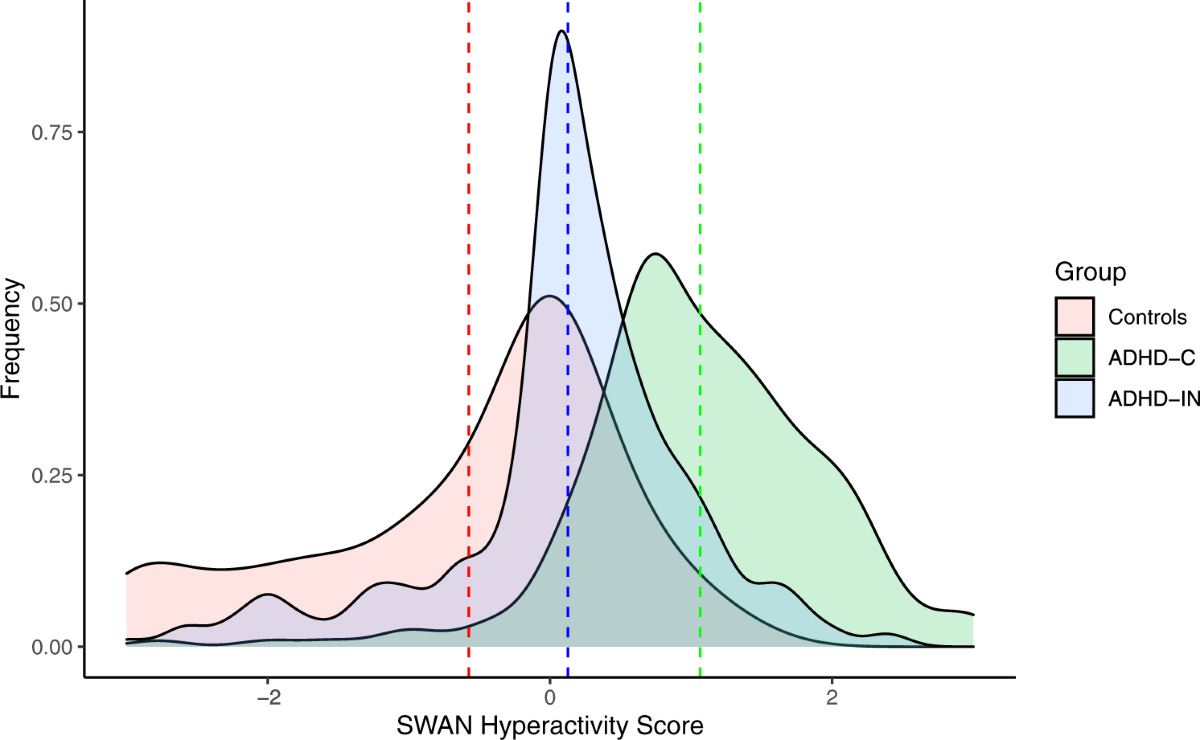

Now let us turn to ADHD. I could almost simply replace the word “hypertension” in the preceding paragraph with “ADHD” and it would remain largely correct, but let’s walk through it. Blood pressure is measured with a sphygmomanometer, while ADHD is assessed with one of many standardized rating scales for ADHD. The bell curve of the scores of one of these scales (Strengths and Weaknesses of ADHD Symptoms and Normal Behavior Scale) is shown below:

There is an overlap of the curves between people with and without ADHD, just as there was a “zone of uncertainty” in the blood pressure distribution in terms of the cutoff for hypertension. To make a diagnosis of ADHD, we need something besides having a score at the higher end of the bell curve. As Spitzer formulated, a disorder in DSM must also show impairment. DSM requires a set number of symptoms, onset of some symptoms in the childhood years, symptoms in at least two different settings, and impairment in daily life. Just as the American Heart Association looked at clinical trial data, the American Psychiatric Association used field trial data to determine where the cut off for ADHD should be. People who score above these cutoffs (and meet the other criteria above for ADHD) clearly show multiple serious problems in their daily lives (e.g., academic and job failure, physical injuries, criminal behavior, substance use, among others). Please see my Substack post, “Why We Must Treat ADHD,” for more details about these problems. The ADHD DSM-5 criteria are no more “arbitrary” than those to diagnose hypertension. Like hypertension, ADHD is caused by several risk factors, although genetics play a much bigger role in ADHD (~80% heritability). Other factors studied include socioeconomic status, nutrition, environmental toxins and perinatal factors. Just as there is no single “biomarker” for hypertension, we do not have one for ADHD. Here is another intriguing point, genes that put an individual at risk for hypertension also raise the risk for ADHD, and vice versa. At this point in science, both hypertension and ADHD stand on equally strong footing in terms of being “diseases.” The same can be said of all the major psychiatric disorders -- schizophrenia, as well as mood and autism spectrum disorders.

In his essay on normality cited at the top of this article, Ahmari goes too far in his critique of psychiatry:

“Psychiatry, too, often used coercive means to discipline “abnormal” people, who happened to comprise almost the entire population. “Normal development” became the obsession of mothers and pediatricians. Children with what we now call autism spectrum disorders were punished cruelly to “correct” their divergence from the neurological norm.”

In the last sentence, he is no doubt casting aspersions on Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) for the treatment of specific problematic behaviors in children with autism spectrum disorders. The view that psychiatry is coercing people to fit into “normality” is an old one among intellectuals and even among some in the mental health profession. By this argument, “normal” is something defined by elites and disadvantaged people are “forced” to conform to it. People in the neurodiversity movement object to ADHD or autism being viewed as “abnormal” and propose that society should “adjust” to people who are different. (The benefits, risks and contradictions of the neurodiversity movement will be the topic of a future Substack post.) Autism, however, is associated with severe long term problems, including social isolation and lack of employment; these outcomes are worse in those with intellectual disability and/or language problems. We cannot make ADHD, depression, psychosis, or autism go away by pretending it does not exist, any more than we can avoid a heart attack by never checking our blood pressure.