The diagnosis of ADHD makes an individual eligible for accommodations in either school or work under the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). These can take several forms: extended time for taking examinations, taking exams in rooms without distractions, or taking “Stop the clock breaks” during exams. Students with ADHD may qualify for selecting classes at certain times of the day when ADHD medication is most active or when the students feel most alert. These are the most popular accommodations; others include recorded lectures, audio textbooks, assistance with note taking, and additional written instructions. These latter accommodations are less relevant in an era when most classes are recorded or streamed, and professors give copies of their PowerPoint notes to everyone. People who had accommodations for their ADHD in high school find that colleges are not required to provide special education-type interventions. Colleges also are not required to alter course work or degree requirements, provide specialized tutoring, or give deadline extensions on assignments. Each case is handled individually, and students and colleges sometimes end up going to court. In 2018, a student sued her college because of her failing grades; she had requested accommodations which included a requirement that professors notify her parents if she missed any assignments! This is not an accommodation that schools are required to give, but if they agree in writing to do so they would have to follow through. The student alleged the college did not do so and as a result, she failed several classes. (In 2020, this case was settled, with the outcome unknown.)

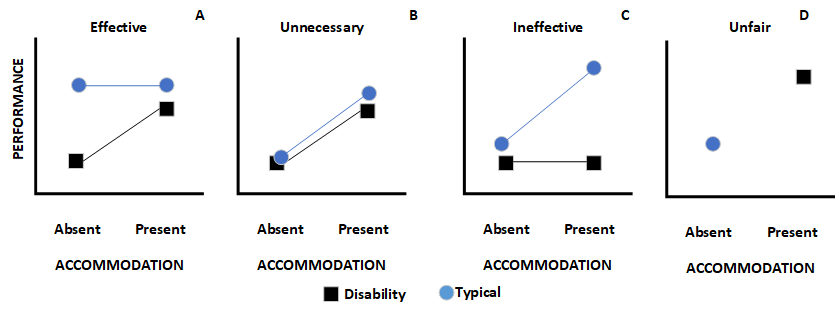

The National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) of the U.S. Department of Education has shown that the number of college students reporting a disability has grown from 5% in 1995 to nearly 20% in 2016, the last year for which data is available. Roughly 40% of these individuals report ADHD or learning disability as their primary disability. Given the large number of students who often seek such accommodations, colleges and universities have strict procedures for granting them and usually require that a student have evidence of a definitive diagnosis prior to enrolling in college. Does the availability of such accommodations create an incentive for claiming a disability, such as ADHD? In the “Varsity Blues” college admissions scandal, one of the techniques the perpetrator used to help a client improve their SAT score was to get a prospective student certified as disabled so they could take the SAT in a room by themselves. This might facilitate cheating or even allow for a substitute test-taker. Do accommodations such as these truly help people with ADHD? Theoretically, an accommodation should be specific to a disorder such that only those with the disorder improve when it is applied. This is best understood visually as shown in the figures below:

Figure A shows a situation in which an accommodation is both effective and fair. The group with a disability shows a deficit in a standard situation, but when an accommodation is made, their performance is the same as the typical group. For instance, a paralyzed person cannot use a keyboard but can use speech-to-text software to create an essay as good as that of a typical person. In Figure B, the accommodation is unnecessary since the disabled and typical groups perform equally prior to the accommodation and with the accommodation. In Figure C, the group with a disability gets an accommodation, but it does not help their performance and is thus ineffective. For instance, a student with ADHD may get extra time on an algebra test, but if they have not mastered the concepts of higher math, the extra time will be of no value. An unfair situation is shown in Figure D in which the accommodation is unnecessary for a group with a disability but is given anyway. The typical group does not receive the accommodation, and now the person with the disability has an advantage and can perform better.

With regard to ADHD, it may well be that commonly used accommodations are not helpful. Let’s look at several studies that have examined this issue. In 2015, Laura Miller and her colleagues studied the effects of extended time for college students with and without ADHD. They administered a standardized reading test to 238 college students with ADHD and 38 controls under three conditions of varying lengths of time. Both groups completed more items in the extended time than in the standard time, but there was no difference between the control and ADHD groups at each time level. This meant that the participants with ADHD did not in fact need the extra time to perform well. A study of 96 students with ADHD in third through eighth grades found no relationship between extended time provided and scores on standardized achievement tests. What about placing a student with ADHD in a separate room for an examination? Robert Weis and Esther Beauchemin randomly assigned over 1,600 college students to take a college placement examination either in a group or a separate room. They categorized the students based on the presence or absence of ADHD and/or learning disabilities, history of having test accommodations in the past, and self-reported history of test anxiety. They found that students with disabilities did worse when they were in a room by themselves and that being alone did not mitigate test anxiety.

A major study published in 2020 by Judith Harrison and her colleagues at Rutgers University examined this issue from a different angle. They randomized middle- and high-school students with ADHD to either receive standard accommodations (organizational support, extended time on assignments and a copy of the teacher notes) or interventions. Interventions were more active steps and included self-management training as well as note taking instruction. These interventions required ”buy-in” from the students, as they had to attend twice weekly after-school sessions for 13 weeks. Perhaps not surprisingly, about half (18/34) of the students with ADHD who were randomized to the intervention group were not willing to fully participate in the interventions (the “unwilling” subgroup). On outcome measures such as binder organization or note taking, the intervention group significantly outpaced the accommodation group, particularly for the “willing” subgroup. The accommodation and “unwilling” intervention groups did show improvements over baseline on some measures but deteriorated as the study progressed. Why were some students with ADHD unwilling to participate in the interventions? The authors state, “According to some of the unwilling students, they did not find the strategies useful because teachers did not expect them to perform these functions” (pg. 33)” (emphasis added). The authors further suggested that the accommodations students with ADHD had already received may have produced a harmful effect, lowering their motivation to develop new skills.

The above study was small, with a total of 64 participants, but it suggested that common accommodations are not particularly fair or successful for ADHD students. As a clinician, I can attest to how popular accommodations are among my college-age patients with ADHD. Nonetheless, I have seen them get into all sorts of academic difficulties which are not attenuated by these types of accommodations. My patients failed courses due to not taking their medication, not attending class, poor sleep habits, and excessive video games and social media use. They rarely took advantage of tutoring or other support services within their university’s disability office. Regrettably, many fell victim to heavy alcohol and substance use. My clinical impression is consistent with what has been described in the literature about the many travails of college students with ADHD.

Based on the research findings presented, we need to reassess the types of accommodations that individuals with ADHD receive in higher education. There is no evidence that extra time on tests or taking classes at a certain time leads to improved performance and might in fact be unfair advantages. Instead, college students with ADHD might benefit from more targeted accommodations. These would include mandatory study halls in the evening and on weekends, life coaching, and additional tutoring. Arthur Anastopoulos and his colleagues have developed a form of cognitive behavioral therapy called Accessing Campus Connections and Empowering Student Success (ACCESS) designed for students with ADHD. It is an 8-week program that educates students about ADHD (symptoms, medication management), helps them develop behavioral strategies (organization, planning, class attendance) as well as adaptive thinking. In a large-scale study, 250 students (two-thirds female) were randomized to receive ACCESS or go to the wait list control group. At the end of the study, the ACCESS participants were significantly more improved in terms of “ADHD symptoms, executive functioning, clinical change mechanisms, and use of disability accommodations” (pg 21). More research on the effectiveness of these types of accommodations is needed. Students might feign or exaggerate an ADHD diagnosis to get special class times or extra time on exams, but no one will feign ADHD to enroll in a time intensive intervention. All students with ADHD would function better in college if they were to take their medication on a regular basis, not just during exam week (See my post, “Why We Must Treat ADHD”).

Of course, creating these more complex interventions would require “buy-in” from both students and institutions. Universities at present are not required to provide specialized interventions. These might be expensive and require higher levels of professional staffing in disability offices. Students with ADHD may not want to do the extra work these interventions entail. Altogether, these studies raise an interesting question: do people have a right to an accommodation that has not been shown to help the disability in question?